Spring 2024 Debate: Is Sex Binary?

Debate: Is Sex Binary?

April 17, 2024

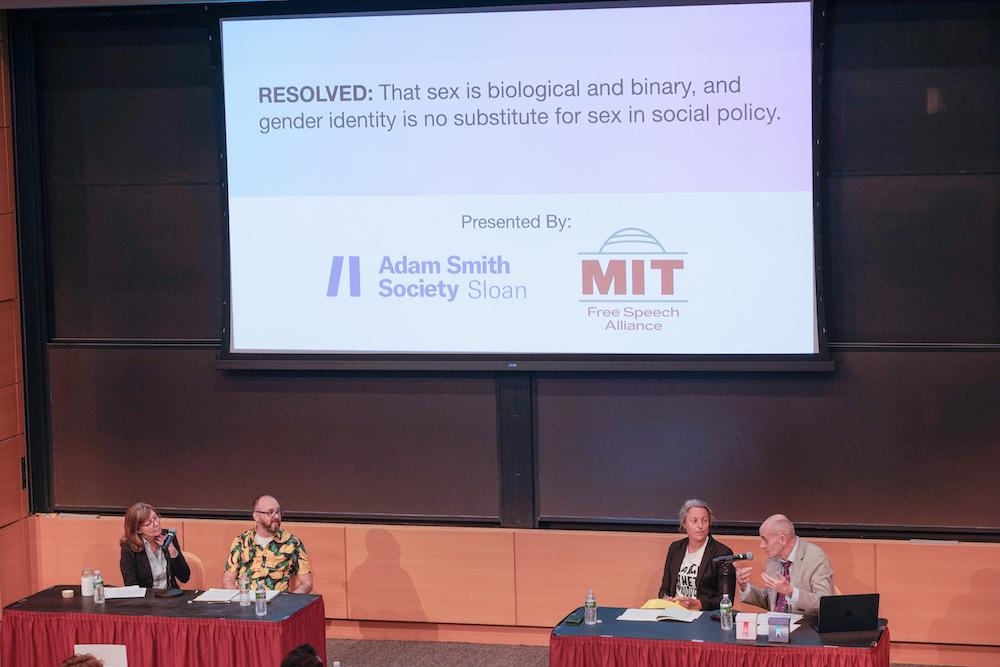

On April 17, the MIT Free Speech Alliance hosted the third in our series of campus debates at MIT. As with our previous debates, we partnered with the MIT Sloan chapter of the Adam Smith Society to present this program to the community, and we were joined by more than 20 additional co-sponsoring organizations. The following resolution was on the table for debate:

Resolved, That sex is biological and binary and gender identity is no substitute for sex in social policy.

Reprising her role as debate moderator was Nadine Strossen, Senior Fellow at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, New York Law School Professor Emerita, and Past President of the American Civil Liberties Union.

The Affirmative Team was Dr. Alex Byrne, Professor of Philosophy at MIT and author of Trouble with Gender: Sex Facts, Gender Fictions, and Dr. Holly Lawford-Smith, Associate Professor in Political Philosophy at the University of Melbourne and author of Gender-Critical Feminism. The Negative Team was Dr. Alice Dreger, American historian and journalist, a Guggenheim Fellow, recipient of the Heterodox Academy’s Courage Award, and author of Galileo’s Middle Finger; and Aaron Kimberly, a trans man, mental health nurse, Director of Public Engagement with the LGBT Courage Coalition, and co-host of the Transparency podcast.

The debate was recorded and livestreamed, and posted to MFSA's YouTube channel. The recording can be viewed below.

Debate photos

Debate recording

Participants

Alex Byrne is a Professor of Philosophy in the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a founding member of the Academic Freedom Alliance. His main interests are the philosophy of mind, epistemology and metaphysics, and the philosophy of sex and gender. His books include Readings on Color, volumes 1 and 2 ( MIT, 1997; co-edited with David Hilbert); Transparency and Self-Knowledge (Oxford, 2018); The Norton Introduction to Philosophy (third edition in preparation, co-edited with Gideon Rosen and others). His most recent book is Trouble with Gender: Sex Facts, Gender Fictions (Polity, 2024).

Holly Lawford-Smith is an Associate Professor in Political Philosophy at the University of Melbourne. Her most recent books are Is It Wrong To Buy Sex? (2024), Sex Matters: Essays in Gender-Critical Philosophy (2023), and Gender-Critical Feminism (2022). She also writes regularly for Quillette and Fairer Disputations.

Alice Dreger, PhD, is an American historian and journalist, Guggenheim Fellow, and author of Galileo’s Middle Finger, published by Penguin Press and named a New York Times Editors’ Choice. She served as President of the Intersex Society of North America, and her work on intersex includes three books plus a TEDx talk viewed over a million times. Her bylines include the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, WIRED, and the Atlantic. The Heterodox Academy bestowed on Dreger its inaugural Courage Award for her championing of free speech and open inquiry, and she now serves on that organization’s Advisory Council.

Aaron Kimberly is a female to male trans man with a rare ovotesticular DSD who lived as a masculine lesbian as a young adult, prior to legally changing sex in 2006. He’s been a nurse with a specialization in mental health since 2008, working in various inpatient and community settings, including the BC Provincial Tertiary Eating Disorders Program, and Foundry, an integrated, multiservice centre for youth. In 2021, he cofounded the Gender Dysphoria Alliance and in 2022, the LGBT Courage Coalition. He cohosts the Transparency podcast, a compassionate yet heterodox conversation on the topic of trans.

Nadine Strossen, the John Marshall Harlan II Professor of Law Emerita at New York Law School and past President of the American Civil Liberties Union (1991-2008), is a Senior Fellow with FIRE (the Foundation for Individual Rights and Education) and a leading expert and frequent speaker/media commentator on constitutional law and civil liberties, who has testified before Congress on multiple occasions. She serves on the advisory boards of the ACLU, Academic Freedom Alliance, Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism (FAIR), Heterodox Academy, National Coalition Against Censorship, and the University of Austin.

Debate Co-Sponsors

For more information about our co-sponsors:

- Adam Smith Society

- Alumni Free Speech Alliance

- American Council of Trustees and Alumni

- Arizona Strategies

- Braver Angels

- Cornell Free Speech Alliance

- The David Network

- Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism (FAIR)

- Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)

- Free to Choose Network

- Harvard Alumni for Free Speech

- Harvard Union Society

Debate Transcript:

A Note on the Transcript: This text was generated by an automated transcription service from the video recording of the live event. While it has been formatted for readability, it may not be a perfect representation of the spoken word and could include transcription errors. For critical reference, we recommend consulting the original video recording.

[0:17] Wayne Stargart: Okay, good evening and welcome. I'm Wayne Stargart, the president of the MIT Free Speech Alliance, and, uh, we are an alumni-led organization that is completely independent from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the MIT Alumni Association. But we're one of the co-sponsors of this event tonight, along with the Sloan School's Adam Smith Foundation and the MIT Students for Open Inquiry and 19 other co-sponsors that you see displayed on the screen behind me.

So on behalf of all of the co-sponsors, I welcome you to this, uh, to being here live for this night's event. I also welcome all the people who are watching right now on the live stream, and we also welcome the thousands of people who will be viewing this event, uh, the recording of this event afterwards, on the MIT Free Speech Alliance YouTube channel.

[1:23] Now, before introducing the moderator and getting on with the program, I wanted to explain why we have these events at all. So this debate series was started in response to a cancellation event a few years ago in which a visiting professor's presentation was canceled over views he had—personal views he had expressed which had nothing to do with his academic work. This was kind of a signal that MIT had lost its traditional tolerance for a divergence of viewpoints and had also lost its ability to engage in respectful dialogue over controversial issues. So we and many of these co-sponsors started this debate series to model for the MIT community how to engage in civil, respectful discourse over issues which could be controversial and maybe, uh, engaging, and also how to do that in a respectful way. And you're going to see that here this evening.

[2:54] Okay. Now it is my honor to introduce our moderator for the evening, as she has moderated all of our debates so far, Professor Nadine Strossen. Let me explain all the reasons why you need to be, uh, applauding. So Professor Strossen is, uh, past president of the American Civil Liberties Union. She's a professor emerita of New York Law School, and she's currently a senior fellow with the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. She writes frequently on this topic and, uh, earlier she had released a book which is relevant even today, obviously, titled HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship. And last year, she released the title of Free Speech: What Everyone Needs to Know. Now, when Professor Strossen is not writing about free speech, she's crisscrossing the country speaking on this topic, and she is here tonight in that same spirit. So Professor Strossen, the floor is yours.

[4:07] Nadine Strossen: Thank you so much, Wayne, and thank you for the kind introduction and for the great work that you and MFSA have done, both here at MIT and with very significant ripple effects far beyond MIT. Regardless of our views about the specific topic of tonight's debate, our debate raises general concerns about academic freedom. As Wayne alluded to, too many people have argued that the issues we're addressing, along with the other issues that have been the focus of MIT's debates, should not be subject to debate at all, even in an academic setting. And polls, including polls that have been conducted by FIRE and by College Pulse, show that many people don't dare to discuss these important topics even on campus for fear that they will be accused of causing harm.

So solely by participating in this debate, all of the participants, although they will obviously disagree on the debate topic, uh, they all agree on the very important point that does not, uh, cannot be taken for granted, namely that these issues are not beyond debate. So, uh, I'm going to use my traditional prop throughout these debates. Uh, don't get too excited or annoyed, depending on your views about Donald Trump. Uh, as this cap declares, we all want to "Make John Stuart Mill Great Again." Uh, and Mill, of course, powerfully explained that we must debate even, indeed especially, our most cherished ideas and beliefs. And what better place to do that than MIT, which is a world leader in science and certainly deserves to be a world leader in scientific inquiry, open inquiry.

[6:45] Okay, now I'm going to, uh, introduce very briefly our distinguished debaters. For more information about their impressive accomplishments, please look at the MFSA website.

Starting with our two affirmative team members, um, they are both philosophy professors. One is from right here at MIT, and the other is from the other side of the world. So first, Alex Byrne, uh, an MIT philosophy professor and the author of Trouble with Gender: Sex Facts, Gender Fictions. And second, Holly Lawford-Smith, a philosophy professor at the University of Melbourne in Australia and the author of Gender-Critical Feminism.

And our negative team: Dr. Alice Dreger, a historian, journalist, and Guggenheim Fellow who is the author of Galileo's Middle Finger. And Aaron Kimberly, an RN and interim co-director of FAIR in Medicine and community engagement director of the LGBT Courage Coalition. So a welcome to all of our distinguished debaters.

[8:00] Next, I'll briefly outline the debate format. Each speaker is going to have an 8-minute opening statement, alternating between the affirmative and negative teams. Each opening statement will be immediately followed by three minutes of cross-examination by a member of the opposite team. Then each team will have five minutes for rebuttal... And then we'll turn to audience questions.

[9:00] So now it's time for our first opening statement from affirmative team speaker number one, eight minutes.

Alex Byrne: Uh, thanks, Nadine. So thanks to the MIT Free Speech Alliance for arranging this event. Um, Holly and I are delighted to be up against Alice and Aaron, two people we very much admire. If it turns out that there's not as much disagreement between the two teams as you were hoping for, don't blame the Free Speech Alliance. Believe me, they tried. But it turns out some people are not prepared to defend their ideas in public.

So the proposition before us is that sex is biological and binary, and gender identity is no substitute for sex in social policy. It's got three parts: sex is biological, sex is binary, and the gender identity bit. In my opening eight minutes, I'm going to concentrate on the first two parts, leaving the third part mostly for Holly.

So before getting into the details, I want to stress one thing. The first two parts—sex is biological and sex is binary—are obviously about biology. The third part, about gender identity, is obviously about social policy. Uh, Holly and I, and this is very important, are not taking the biology textbook as a guide for organizing society. We are not saying, "Sex is biological and binary, so of course the military should be stationed outside bathrooms," or anything like that. The point, instead of discussing the first two parts, is just to get clear on some basic facts about, uh, sex and clear up some common confusions.

Okay, so let's turn first to "sex is biological." What does that mean? How could sex fail to be biological? Well, Holly and I take "sex is biological" to mean that sex is not socially constructed. Sex is not, as Judith Butler writes in Who's Afraid of Gender?, "established by various cultural and social means."

I'll spend most of my time on the second part of the proposition: "sex is binary." Now here, things get a little tricky because "sex is binary" is understood in two ways, leading to people talking past each other. On the first understanding, "sex is binary" simply means there are exactly two sexes or reproductive classes: male and female. That is, there are exactly two sex boxes... anyone with a sex is in one of the boxes.

So I can be quick defending "sex is binary" understood as there are exactly two sex boxes. I doubt that Alice or Aaron want to defend the view that there are fewer than two sex boxes or that there are three or more. Last time I looked, the biology textbooks were still talking about males and females and hadn't added any new sexes. The textbook account of males and females in terms of small and large gametes—sperm versus eggs—uh, has stayed the same for well over a century.

Okay, so that's the first way of understanding "sex is binary." What about the second way? Well, keeping it simple, you can think of it as adding something to the claim that there are two sex boxes. Yes, there are two sex boxes, but in addition, everyone is either in this box or this one... Now, our position on this second understanding of "sex is binary" is a bit nuanced. So what we want to say is that there aren't any clear exceptions to it. That is, there are no clear cases of sexless humans or humans who are both sexes at once.

Here, the discourse about the sex binary takes a very regrettable turn. People with so-called intersex conditions... are paraded around at this point... The fact is that if you examine DSDs, you'll find that people with them almost always readily slot into one of the two reproductive categories.

Okay, so let me now quickly say something about the third part of the proposition, about sex and gender identity... For our team's purposes, it can simply be interpreted as gender self-identification, that is, what sex you say you are. So what we're claiming is that sex self-identification, sex self-ID, can't replace sex in social policy... Although we think that sex is sometimes better than sex self-ID, that doesn't mean it always is. Generally, people should be allowed to associate as they see fit. If you want to have a dating app open only to those whose self-ID is female, go for it. But if you want to have a dating app only for females, you should be allowed to go for that too.

[17:21] Alice Dreger: (cross-examination) I thought I would begin with asking you, so how do you define sex?

Alex Byrne: Um, well, the textbook definition of sex is in terms of, um, gamete size. To a first approximation, you're male if, um, you have the body plan which produces small gametes, and you're female if you have the body plan that produces the larger gametes.

Alice Dreger: And a follow-up question, do you have any concerns with the idea of sex being policed in social spaces?

Alex Byrne: Um, oh, sure, yes... I don't think there should be sex inspections outside bathrooms, for example. Um, you know, these social norms do much better when people just naturally follow them.

Alice Dreger: But if you were to allow people to decide for themselves, that is essentially what we're talking about with gender identity, right?

Alex Byrne: No, the point is that, look, for some cases... there's a case in, uh, Australia, which is in the courts right now, called, believe it or not, Tickle v. Giggle, which is all about whether it's legal to have a dating app that's open only to females, which can exclude people who, um, are male but who self-identify as, uh, as females. And I think our position is, uh, that that should not—it should not be illegal to have a dating app of that sort.

[20:58] Alice Dreger: (opening statement) My orientation is that of an historian of medicine and science who has tracked centuries of human attempts to define sex... The chief points I want to make are these: First, that sex development is, in fact, complex and varied, and sex development is actually a lifelong process... Second, that arguments in favor of understanding sex as simply binary are often inconsistent in implementation. The same people who tell us sex is about gonads or gametes tell us sex is really about hormones when they arrive at a sports stadium. Third, we can both believe in biology, as I do, and make reasonable social policies without having to go back to 19th-century concepts of true sex. And we should.

So, sex development is complex and varied. There are more people on the planet with intersex conditions than there are Jewish people, and I don't think either population should be treated as ignorable rounding errors in the development of social policy... It's nonsensical to say that gamete production is what makes us male or female. I've stopped making eggs, but I'm surely female. A male-typical or a female-typical child whose gamete-producing ability is permanently thwarted by trauma or by chemotherapy is still rightly recognized as male or female.

Back to sex variations. Genetic mosaicism means you can have XX in some of your cells and XY in others. A male can be born with XX chromosomes due to translocation of the SRY gene. A person who is female-typical in terms of her genitals and brain development can be born with XY chromosomes and testes because she lacks androgen receptors, a condition called Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome, or AIS... Please consider what it will mean to a girl with AIS and her family if you decide she is definitionally male.

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia, or CAH, is an inborn condition that can result in a wide variety of sex developmental pathways. Among those, it means a genetically and gonadally female child can be born looking like a typical boy... I don't let my ovaries tell me what to do, and I don't think you should let your ovaries tell you what to do.

We can both believe in biology, as I obviously do, and make reasonable social policies without having to go back to 19th-century concepts of true sex. And we should. These policies can be based on what we recognize as legal fictions—categories we create to manage competing interests. Most importantly, we can police behavior rather than biology. If the problem is sexual predation... let's deal with those problems. Let's deal with behavior, not police identities.

[26:49] Alex Byrne: (cross-examination) Alice, thanks so much. Uh, first question, how many sexes are there?

Alice Dreger: I think that depends on the time and the place and the way you're categorizing things. So as a historian, I would say that's a question that's answered within particular cultures... There are categories, there are features of sex which clearly exist on the spectrum... I don't think it's really sensible to say biology tells us this, therefore that is what is absolutely true.

Alex Byrne: Okay, so you at least agree that some humans are male and some humans are female?

Alice Dreger: Some humans have all of what we consider to be the male-typical patterns, and some humans have all of what we consider to be the female-typical patterns, yes.

Alex Byrne: You mentioned Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia... do you think that XX individuals with CAH are female or not?

Alice Dreger: I think they're genetically female, they're gonadally female... whether or not their brains end up female-typical or male-typical also depends on the level of hormones... I think life is more complicated than two little boxes. I think science knows that sex is much more complicated.

[30:59] Holly Lawford-Smith: (opening statement) Uh, as Alex said... we take the question of whether gender identity is a good substitute for sex in social policy to be logically disconnected from the question of whether sex is biological and binary... Social policy in the context of this debate refers to anything public where sex has historically been the basis of organizing people and where there is now some pressure... to shift to gender identity instead. Some examples include prisons, sports, domestic violence refuges... changing and fitting rooms, hospital wards, schools, short lists, prizes, festivals, and the collection of census data.

There are two ways for us to approach this policy part... One is to argue wholesale for all spaces at once, and the other way is to go space by space... The other strategy, and the one we'll take tonight, is to go space by space... Some spaces are easier for one side or the other to claim. In my view, sports are the best case for sex, and bathrooms are the best case for gender identity. But I'm quite confident that we've all heard more than enough about sports and bathrooms, so I'm going to focus instead on the less-discussed case of, uh, gay and lesbian spaces.

If inclusion should be decided by gender identity rather than sex, then the gay sauna should admit females who identify as gay men, and the lesbian speed dating event should admit males who identify as female and lesbian.

A group called The Lesbian Action Group in Australia last year applied to the Australian Human Rights Commission for an exemption to anti-discrimination law in order to be able to hold a series of cultural events for lesbians... The group used the phrase "lesbians born female" in their application to make it absolutely clear... and their application was rejected among other reasons because it was exclusionary of trans women who considered themselves to be lesbians... So the issue was the Lesbian Action Group wanting to use sex, not gender identity, as their grounds for inclusion. So which should it be?

[38:53] Aaron Kimberly: (cross-examination) My first question is, how would you implement sex-based policy if it weren't for gender identity? How would you implement sex-based policy?

Holly Lawford-Smith: I'm not sure if implementation is even the right word. I think we're trying to make the strongest case we can that sex is still relevant, um, and we want people to get behind that.

Aaron Kimberly: In terms of lesbian spaces, do you feel just for clarity, do you feel that... lesbian spaces should include trans men or trans women?

Holly Lawford-Smith: Trans men, yeah... We are fighting for the right to be allowed to have events for lesbians only... or one app out of all of the apps that are trans-inclusive to be able to have one app that is trans men inclusive rather than trans women inclusive when it's a women-only space.

[42:22] Aaron Kimberly: (opening statement) So I'm going to focus on definitions, um, because there are two competing definitions of gender identity: one which is political and one which is evidence-based... The political definition I will call a "disembodied model," which is an invisible internal feeling. The evidence-based definition I'll call an "embodied model," which is a self-perception of sex... I think a strong case can be made for an embodied model which integrates material reality with its psychosocial meaning.

In the 1960s, professor of psychiatry Robert Stoler coined the term "gender identity" in context of researching how all people come to understand our sex and its meaning within a social context. He identified three key variables... we could think of these as three glass lenses stacked on top of one another... and those three lenses are: biological sex, cultural context, and other biological factors, such as the impact of testosterone on female development. If one of those lenses becomes cloudy, it complicates the entire view.

Stoler's model of gender identity, rooted in both biological and psychosocial realities, is adequate for the writing of inclusive and protective policy. It provides us with an evidence-based tool for thinking through ethical dilemmas and conflicts of interest.

[49:21] Holly Lawford-Smith: (cross-examination) Can I just maybe start by getting you to say a little more about the cultural context in the Stoler model?

Aaron Kimberly: Sure... it was about societal, um, you know, feelings about gender nonconformity or about, um, sex differences... which influences sex assignment, but it could be also societal responses to homosexuality and gender nonconformity.

Holly Lawford-Smith: Okay. What do you think about the rule, "if you pass, you pass?"

Aaron Kimberly: Yeah, I don't think passing is really the issue... I am female and I have a beard. So, um, I don't think passing is the issue.

Holly Lawford-Smith: So if you wanted to use female spaces, you would fail on that rule, but you think you should be able to use female spaces?

Aaron Kimberly: It depends on the spaces... In the case of lesbian spaces, there are a lot of lesbians that are in relationships with trans men... In the case of bathrooms... because I know I do pass as male most of the time, I don't want to be disruptive... I would personally use male bathrooms because I think if I were to walk into a woman's bathroom, I would make women feel unsafe. And I think if passing trans men can use women's bathrooms, then what is to prevent any man from walking into a woman's bathroom and say that they are a passing trans man?

[52:29] Rebuttals

Alex Byrne (Affirmative): So one thing she said was, well, there are different kinds of sex. You can be hormonally female, chromosomally female, genitally female, and so on... But you shouldn't confuse these layers of sex with sex itself... The very explanation of these layers of sex presupposes some absolute notion of being male or female.

Holly Lawford-Smith (Affirmative): It would be good to say something about the state of the debate on this topic... None of them have involved the most vociferous opponents of the gender-critical side: people who deny the reality of biological sex, people who think sex is never an appropriate basis for social policy... Some people with those views were invited to this debate and they refused, and I think this has to stop... The proponents of gender identity instead of sex in all cases need to step up and make their case.

Alice Dreger (Negative): I think Alex is caught in a hopeless tautology... he basically keeps saying, "This is how we define sex, therefore this is how sex is defined."... Sex is obviously not binary. We don't have to name a number of sexes to recognize that sex doesn't come in two simple categories... Our attempts to clearly categorize things that are not clearly categorized is about social politics... At the end of the day, a lot of what we're reacting to... is again the fact that our brains are working on sex all the time.

[1:03:40] Audience Q&A

Nadine Strossen: Now it's time for the audience Q&A... I'll just start with this side and alternate.

[1:04:17] Audience Member: Question directed to Alice. Would like to say a couple words about Lia Thomas.

Alice Dreger: Yeah, so here's a good case where I think it makes sense to begin to consider the possibility of creating hormone classes within sports... She obviously has had a male puberty, continues to benefit from male typical hormones... In that case, I think the logical thing to do is to create a category that is a biologically based category and to recognize we're doing it for social purposes. Right? So we have age categories in sport, we have, um, weight categories in some sports, we can have hormone categories in some sports.

[1:07:20] Audience Member: Hi, this is a question for Alice... Is there a kind of consistent model you could apply, like a spectrum or, in fact, a set number of sexes... or is it just this ever-changing kind of variable thing that no one really understands?

Alice Dreger: No, we do understand it... What I'm saying is that different cultural groups will make different decisions based on the social need... The way that sex is defined currently in medicine, for example, is... it's defined honestly as a five-sex system where basically they have males, females, DSD with ovaries, DSDs with testes, and DSDs with ovotestes... That's where medicine is right now.

[1:10:01] Audience Member: What I really haven't heard much about is how these, uh, divisive issues, uh, affect society as a whole... I'm really concerned that, uh, the transgender craze, if you will... may be partly or largely due to social contagion.

Alex Byrne: One issue is, uh, should transgender women be allowed into the, the, uh, female prison estate? But even if you think the answer to that is no, um, I would think you don't want to put them in the male estate for sort of obvious reasons... There could be a third estate.

Aaron Kimberly: I absolutely can tell you that the majority of people that I saw and assessed didn't have any of the known types of gender dysphoria, um, which is why I left my role, um, and we're pushing back on these practices that are eliminating meaningful assessment.

[1:13:51] Audience Member (Lisa Selin Davis): My question for Alice would be, based on this understanding of gender identity as declaring your own sex to society, what is a non-binary person?

Alice Dreger: I think non-binary, I'm talking about it as a self-identification category... You know, forever people have recognized that there are gender non-conforming children... what I want to say is that whatever all that science says, the reality of the lived human experience is that you're in this complicated... dialogue occurring between biology and culture, and you're trying your best to make sense of where you fit in all of that.

[1:18:34] Audience Member: Let's focus on the future for a moment... Is this division really meaningful in the future? Like, does this division entail moral difference?

Holly Lawford-Smith: A lot of the gender-critical feminists... I think a lot of their goal is some further future where there is not, at least what we would now call, a gender distinction, and the sex differences are minor... but they think that what it takes to get to that future of sex equality is to protect women's interests in the short term.

Alice Dreger: Women are always going to reasonably be worried about males having them in spaces where they could be harmed. Right? Women are going to reasonably fear rape... and I don't think they're going to go away.

[1:22:33] Audience Member: If not gender or sex... under what circumstances would it be acceptable for a person or persons to engage in exclusionary behavior... Tickle v. Giggle as an example.

Alice Dreger: In terms of my private behavior, it makes total sense to me that I should be allowed to create those boundaries. Again, where it becomes difficult is the place where we have government funding, uh, an open public space.

Holly Lawford-Smith: What the question was getting at is... it's not of course in our own home we can do whatever we like... Tickle v. Giggle is about there being one social media app that screens out all biological males.

Alice Dreger: I don't have a problem with the idea that there might be apps set up to be female only.

[1:28:01] Audience Member (Don Lamp): I am a male... I wasn't assigned male at birth, I don't identify as a male, I'm a male. It's ontological. And I just wonder whether folks like myself are permitted to do that... or whether it's okay for me to be a male.

Aaron Kimberly: You know, in the early days when people started taking hormones and transitioning... at no point did it ever occur to me that our very concept of what biological sex is would be dismantled. What we were asking for is some legal wiggle room... I absolutely disagree with what's happening in terms of dismantling our systems and our very understanding of what biological sex is.

Alex Byrne: Yeah, I mean, you're definitely male. There's nothing to be ashamed of, though... I should point out that, you know, these guys are responsible for like 95% of the homicides worldwide, but...

[1:33:16] Nadine Strossen: We've got a lot more questions, but... I was told we have time for only two more questions. Here's what I'd like to propose: that everybody who's standing at a microphone can briefly ask a question, and then I will let each of the debaters have one minute to respond to whatever they choose to among all of those points.

[1:33:42] Audience Member: I think this is mostly for Aaron... you seem to be embracing this idea that gender does come from something actually scientific, and if that's the case, then isn't gender biological, and does this not mean that the idea that gender is a social construct is actually not true?

[1:34:36] Audience Member: Alice, you uh, made a statement when you were distinguishing between male and female characteristics and... you mentioned that, well, there were different mental outlooks and different choices of professions... does that sort of, uh, undermine the arguments for disparate impact?

[1:35:05] Audience Member: So I hope we can agree that sexual dimorphism was selected for evolutionarily... and I'm concerned that, uh, if we detach ourselves from the ability to start from reality and then craft a humane social policy... we might be kind of heading down the road into what you know, Greg Lukianoff calls "reverse cognitive behavioral therapy."

[1:36:32] Audience Member: I just wanted to ask about... whether especially this team recognizes any potential harms for the ways in which gender identity is used in social policy... when I recently applied to a conference, you have to... pick your gender, and there's a whole list, and one of them is "gender non-conforming woman."... It seems like when I pick "woman," I am somehow... saying I'm a "gender-conforming woman."

[1:37:51] Audience Member: My question is mainly for Professor Dreger... would you say that, uh, lesbians or gay men or otherwise gender non-conforming people are less female or male than their straight counterparts or gender-conforming counterparts?

[1:38:44] Audience Member: Can we say that sex exists on a spectrum, um, with female on one side and male on the other... but also binary?

[1:39:15] Audience Member: Coming from a more kind of policy perspective... who should decide what the gender/sex segregation should look like, and how should they go about that decision?

[1:39:54] Nadine Strossen: Thank you all very much for these great questions... I'll give them each one minute to address whichever subsection... they choose to. And why don't we just start in that order: Alex, Holly, um, Aaron, and Alice.

Alex Byrne: Uh, okay, there's so much there. I'll just pick one at random. The "sex is a spectrum" uh, question. So even if it turned out—sex is not a spectrum—but even if it turned out that sex is a spectrum, still sex could be, uh, important, uh, for social policy... for example, weight is on a spectrum, but that doesn't stop weight from being important when it comes to boxing classes.

Holly Lawford-Smith: On the last question about, uh, who decides, especially where it's governments making policy, I think the important thing is just to take all stakeholders' interests seriously, and that's really not happening in some countries... And then just... the gender-critical feminist goal is to rescue the sex-gender distinction... so long as we can make sense of the history of how female people... have been treated, we've got gender on the external understanding, the treatment... I've got everything I need. I don't need to talk about gametes, maybe.

Aaron Kimberly: Um, I wanted to answer the question about, uh, just defining gender identity a little bit better... It's important to remember that when Stoler coined the term, "gender" was synonymous with "sex," and it was long before identity politics. So really, all it meant was an awareness of sex... I think that term has been very corrupted, um, by identity politics and postmodernism... I really don't understand what the word "gender" means... I think I am masculinized because I was exposed to testosterone. That's a biological issue. It doesn't make me male, but it makes me very masculine.

Alice Dreger: Those were so many great questions... Sex is not simply a spectrum because sex is made up of so many different things... Some of them exist on a spectrum. So, for example, hormones are a spectrum... breast development is on a spectrum... genital/phallic development... is on a spectrum... But, um, the SRY gene, it's either there or it's not there, so that's a binary sex element there... At the end of the day, you live where you live, right?

[1:45:01] Nadine Strossen: Okay, I'd like to thank the audience for great questions, the speakers for great presentations. And Alex and Holly, uh, get the closing words.

Alex Byrne: Oh yeah, thanks. Yeah, so we have a little gift for Alice and Aaron... It's slightly awkward because, um, Alice doesn't like sex boxes, and, uh, and Aaron just said that he's female... but I think we'll just go with the superficial appearances. So pink for Alice and blue for Aaron. (Presents gifts)

Nadine Strossen: Thank you very much. That closes the proceeding. (Applause)