Spring 2025 Debate: Closing the Gender Gap in STEM

Debate: Closing the Gender Gap in STEM

April 30, 2025

On Wednesday, April 30, 2025, the MIT Free Speech Alliance, joined by the MIT Open Discourse Society, hosted the fifth in our series of campus debates at MIT. The resolution and debaters were as follows:

Resolved, We Must Close the Gender Gap in STEM

Affirmative Team: Jennifer Roecklein-Canfield, Professor and Chair of Chemistry and Physics at Simmons University and Pamela R. McCauley, Dean of the School of Engineering at Widener University.

Negative Team: Christina Hoff Sommers, Senior Fellow Emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute, and Cory Clark, Behavioral Scientist at the University of Pennsylvania and Executive Director of the Adversarial Collaboration Project.

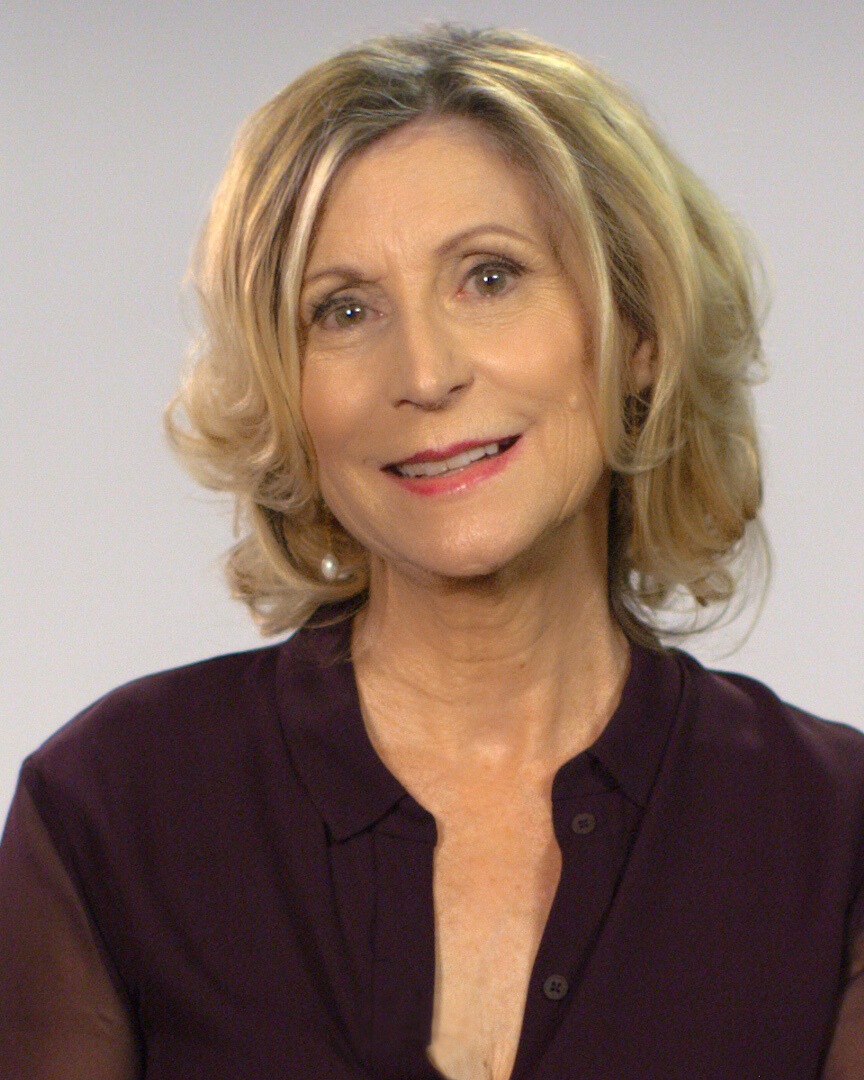

Moderating this spring's debate was Linda Rabieh, Senior Lecturer in the MIT Concourse learning community and a Co-Director of MIT's Civil Discourse Project.

The debate was recorded and posted to our YouTube channel. The debate is embedded below for viewing, as is a slideshow of photos from the evening.

We look forward to returning with our debates in Fall 2025!

Debate Recording

Debate Photos

Participants

Jennifer A. Roecklein-Canfield is a Professor of Chemistry at Simmons University and an accomplished research Biochemist with over 30 years of experience. She has mentored more than 100 undergraduate women in STEM, fostering the next generation of scientists. Her innovative teaching and research have earned national recognition from multiple professional organizations.

A dedicated advocate for gender equity in STEM, Dr. Canfield serves on the Women in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Committee for the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (ASBMB) and was elected an ASBMB Fellow in 2024. She is also a member of the Massachusetts Governor’s STEM Advisory Council, working to expand high-quality STEM education across the state.

Dr. Canfield is the Southern New England Team Leader for the National Girls Collaborative Project (NGCP) and the Chair of the Steering Committee for the Massachusetts Collaborative for the Million Women Mentors Initiative, both aimed at encouraging and supporting girls in STEM. Additionally, she serves on the Upper Middlesex Commission for the Status of Women, advocating for the economic and social empowerment of women and girls.

Her career is marked by a deep commitment to creating opportunities for women in science at local, regional, and national levels, ensuring equitable access to STEM education and careers.

Pamela R. McCauley is a pioneering Industrial Engineering researcher, entrepreneur, and STEM advocate known for her contributions to human factors, ergonomics, biomechanics, and leadership in STEM. Currently serving as the Dean of the School of Engineering at Widener University, she has previously held leadership roles at the National Science Foundation and North Carolina State University and was a Martin Luther King, Jr. Visiting Associate Professor at MIT. An award-winning educator and accomplished author, Dr. McCauley has published extensively, including a best-selling ergonomics textbook and leadership books aimed at empowering women in STEM.

Christina Hoff Sommers is a senior fellow emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where she studies the politics of gender and feminism, as well as free expression, due process, and the preservation of liberty in the academy. Before joining AEI, Dr. Sommers was a philosophy professor at Clark University.

She is best known for her defense of classical liberal feminism and her critique of gender feminism. Her books include “Freedom Feminism—Its Surprising History and Why It Matters Today” (AEI, 2013); “One Nation Under Therapy” (St. Martin’s Press, 2005), coauthored with Sally Satel; “The War Against Boys” (Simon & Schuster, 2001 and 2013), which was named a New York Times Notable Book of the Year in 2001; and “Who Stole Feminism?” (Simon & Schuster, 1995). Her textbook, “Vice and Virtue in Everyday Life,” currently in its ninth edition, is a bestseller in college ethics.

Cory Clark is the Executive Director and Co-Founder (along with Professor Philip Tetlock) of The Adversarial Collaboration Project at University of Pennsylvania and a Visiting Scholar in Management in the Wharton School. She received her PhD from University of California, Irvine in Social and Personality Psychology, and previously worked as an Assistant Professor at Durham University in the United Kingdom and the Director of Academic Engagement for Heterodox Academy.

She is interested in biased evaluations of science, especially among scientists themselves. She has studied how moral and political concerns interfere with academic freedom and pursuit of truth. Lately, she has become interested in how the culture of academia has changed (in favor of equity over merit and harm reduction over academic freedom) as female scholars have come to dominate the institution.

Linda Rabieh (Moderator) is a Senior Lecturer at MIT. She has taught political philosophy there since 2010, primarily in Concourse, an interdisciplinary program in the humanities and sciences, but also in the political science and philosophy departments. Linda received her Ph.D from the University of Toronto and is the author of Plato and the Virtue of Courage, which won the inaugural Delba Winthrop Mansfield prize for excellence in political science. She is also the author of numerous articles that explore the political thought of ancient and medieval thinkers, including Thucydides, Plato and Maimonides. She has been the recipient of a National Endowment of Humanities Independent Scholar Fellowship and various awards and fellowships at MIT. For the past nine years, Linda has been co-director of an annual January study program for MIT students to Greece and Rome, and, more recently, she became one of the faculty directors of the Civil Discourse Project at MIT. She writes and teaches courses on ancient and medieval treatments of ethics in war, political ambition, and the extent and limits of knowledge.

Co-Sponsors

Debate Transcript:

A Note on the Transcript: This text was generated by an automated transcription service from the video recording of the live event. While it has been formatted for readability, it may not be a perfect representation of the spoken word and could include transcription errors. For critical reference, we recommend consulting the original video recording.

[0:00] MFSA Speaker: ...our growing alliance, or just come argue with us at the next event. It's what we do best. Speaking of next event, next Wednesday, the MFSA is hosting... Janara Nirenberg, author of the new book Trust Your Mind: Embracing Nuance in a World of Self-Silencing. Trust Your Mind is praised by former ACLU president Nadine Strossen as a book that should "inspire renewed appreciation of and engagement in the critical thinking and open discourse that are so essential for flourishing in individuals and society alike."

It will be held at 6 p.m. at the Cambridge Innovation Center, um, right across the street, um, at One Broadway, just down the road. Um, we will have, um, beer, wine, uh, and non-alcoholic beverages, followed by discussion and book signing. The event is free, and free copies of the book will be available to those who join. Take the info cards... Oh, there's the slide. And there's cards available, um, if you're interested.

[1:02] But before we dive into tonight's important discussion on closing the gender gap in STEM, I'd like to warmly welcome and introduce our moderator, Linda Rivia. Linda is a senior lecturer in the MIT Concourse program, where she has taught philosophy since 2010. She's also a founder and co-director of MIT's Civil Discourse Project, which fearlessly brings hot-button topics into the debate sphere. She authored Plato and the Virtue of Courage, which won the Delba Winthrop Mansfield Prize for excellence in political science. Linda is a true champion of free expression, viewpoint diversity, and academic freedom throughout all of her work at MIT, including her recently developed class, "Talking Across Differences." We're very fortunate to have her guide tonight's debate with her wisdom and her wit.

On behalf of the MIT Free Speech Alliance and all of our sponsors, thank you again for being here. Let's make this an evening of thoughtful debate, disrespectful disagreement, and above all, free speech. To our debate teams, don't worry. The only thing more nerve-wracking than finals at MIT is a room full of curious STEM people armed with vigorous opinions and feedback. But I have no doubt you are well prepared for this group of friendly skeptics. You've got this. And Linda, the floor is yours.

[2:16] Linda Rivia: Great, thank you very much. So, thank you. Um, I'm grateful to the MIT Free Speech Alliance and all the co-sponsors for organizing this debate. Um, since its founding in 2021, the MFSA has been an essential partner here at MIT in fostering lively, vigorous debate that promotes the highest purpose of the university: the pursuit of truth.

MIT is a world leader in the research and development of math, science, and technology. And it is so because it's a community of deeply curious individuals who want to understand the world as much as to improve it. To understand the world, however, includes knowing the nature of the human beings who inhabit it. And to improve it requires understanding what it means to live well. And while these questions don't involve integrals or wave functions, they can be just as vexing, if not more so. After all, they touch on issues about which we human beings have a tremendous amount at stake.

[3:25] So consider the resolution for tonight: Resolved, we must close the gender gap in STEM. This topic inevitably addresses nothing less than questions of fairness, justice, goodness, nature versus nurture, and the inevitability of chance. No wonder we tend to shy away from discussing it. But to be true to MIT's mission, we must do so. If we shrink from examining an issue because it might be perceived as offensive, hostile, or immoral, we will be unprepared for the tasks of allocating limited funding resources and establishing policy priorities, both of which require we see issues clearly, rather than as we want or hope them to be.

Moreover, our own grasp of the world and of the human situation will be impoverished in so far as we have failed to subject our opinions about these things to rigorous examination. MFSA debates are crucial to advancing these goals because, most importantly, they provide an opportunity to have those conversations that we tend to avoid. They push us to confront uncomfortable positions and thereby to learn something, even if in the end what we learn is a more solid foundation for our original view. So these debates contribute to the vital spirit at MIT that no topic, however unpopular, is simply off-limits. And indeed, that it is especially the unpopular topics that must continue to be addressed. And as a STEM institution with close to gender parity among undergraduates, we are perhaps an especially good place to host such a discussion.

[5:27] So without further ado, let me introduce to you the highly qualified and distinguished women of our debate teams. And then I will briefly outline the rules for the debate, uh, whose resolution you have right before you. Uh, Resolved: We must close the gender gap in STEM.

So for the affirmative team, we have on my left, Jennifer Rocklin Canfield. Um, she's a professor of chemistry at Simmons University, and in addition to over 30 years of research... Dr. Canfield's career has been dedicated to STEM education... and by creating opportunities for women in science at local, regional, and national levels... She's mentored more than a hundred undergraduate women in STEM, fostering the next generation of scientists.

Our second member of our affirmative team is Pamela McCaulay. Um, she is a pioneering industrial engineer, researcher, entrepreneur, and STEM advocate... Dr. Macaulay has held leadership roles at the National Science Foundation and North Carolina State University, and was a Martin Luther King Jr. visiting associate professor in AeroAstro at MIT... Currently, Dr. Macaulay serves as dean of the school of engineering at Widener University.

[8:00] Now, representing the negative side of the resolution, um, we have, closest to me, Christina Hoff Sommers. She is a senior fellow emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute, where she studies the politics of gender and feminism, free expression, due process, and the preservation of liberty in the academy... Dr. Summers is best known for her defense of classical liberal feminism and her critique of gender feminism. She's the author of many books... Who Stole Feminism?, The War Against Boys...

And last but not least, uh, Corey Clark. Um, is a behavioral scientist with a PhD in social and personality psychology. Her research includes the study of biased evaluations in science... and how moral and political concerns interfere with academic freedom and the pursuit of truth... Currently, Dr. Clark is the executive director and co-founder of the Adversarial Collaboration Project at the University of Pennsylvania. This project seeks to promote truth over bias through said adversarial collaborations, in which disagreeing scholars mutually design research procedures to test their competing hypotheses.

[10:44] Uh, now for the debate format, there will be about 50 to 60 minutes total for the debate, which will leave 20 to 30 minutes for questions from the audience. We will alternate teams, beginning with the affirmative, uh, so that each speaker has eight minutes, followed by two minutes of cross-examination from the opposing team. Then each team will offer a five-minute rebuttal to close the debate portion of the evening. Um, and we have a timer sitting down here in front and I have a gavel, which I wish I had in class. I may steal it from you, Peter. Um, so, um, now please let me turn it over to the first speaker of our affirmative team.

[11:38] Pamela McCaulay: Thank you. Thank you so much. It's—good evening, everyone. It's a pleasure to be here. Uh, I will begin from the affirmative team. So I want to say the secret to a strong economy is women. Uh, I wish I had said that statement, but these powerful words come from business leader Sheryl Sandberg, and they capture a truth that is both simple and profound. When we fully tap into the talent of our entire population, we strengthen not only our companies, but our communities, our economy, and our national standing.

Today, I rise in full affirmation of the proposition that the United States must prioritize closing the gender gap in STEM—science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—as a matter of national security, economic prosperity, and global leadership. This is not simply about equity, though equity is important. It's about fully engaging America's talent pool to unlock innovation, drive economic growth, ensure national security, and maintain leadership in an increasingly competitive world.

I would like to take a few moments to make four points to stress the validity of the proposition that the United States must prioritize closing this gender gap.

First, closing the gender gap in STEM is a powerful economic imperative. The European Institute on Gender Equity projects that achieving gender parity in STEM could increase GDP per capita in the EU by 3% by 2050. Comparable gains are also expected in the United States, as according to the Council on Foreign Relations, women's participation increase in STEM careers could add $299 billion in women's cumulative earnings in the US over the next decade alone. Today, women represent nearly 50% of the overall workforce, yet we only hold 28% of the STEM jobs in this country. Even more stark, in engineering occupations, women account for only 16% of our nation's engineers. So folks, the economic cost of sidelining women's talent is significant.

Secondly, closing the gender gap is crucial for driving innovation and global competitiveness. Uh, it's no coincidence that companies that are renowned for innovation tend to prioritize inclusion and diversity... Research published in the Harvard Business Review shows that diverse teams consistently outperform homogeneous teams in creativity, problem-solving, and decision-making. Moreover, a landmark study by Credit Suisse found that companies with 15% or more women in senior leadership had achieved 50% higher profitability compared to those with lower female representation. Now, despite these facts... there still remains a troubling gap. While women earn 59% of the bachelor's degrees overall, we only earn 35% of STEM degrees, and just 22% of engineering degrees and 19% of computer science degrees.

Thirdly, closing the gender gap is vital for national security. In the 21st century, military readiness, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and space exploration are increasingly dependent on scientific and technical expertise... Yet women remain underrepresented in these critical fields. Once again, allow me to cite some statistics... today women comprise only 26% of computer workers and 16% of engineers. Now, as we face these global challenges for dominance in technologies like quantum computing, hypersonics, and cyber defense, countries like China are aggressively expanding their standard workforce... A workforce that excludes half of its talent cannot compete in this race. Period.

Finally, the gender gap in STEM jeopardizes America's ability to lead globally in technology and innovation. I want you to listen very closely to this: In 2020, India awarded 2.5 million science and engineering degrees. China awarded 2 million. The United States awarded 900,000. Folks, we got to do better than this. Our competitors are growing their STEM workforce faster and tapping larger percentages of their population. To maintain leadership, the United States must leverage all of its available talent. Women, representing half of our population, are the single largest untapped source of STEM expertise we have.

In conclusion, closing this gender gap in STEM is a strategic necessity for the United States. It will unlock hundreds of billions of dollars in economic growth, supercharge innovation... and strengthen our national security. This is not about lowering standards, folks. It is about raising opportunities. It's about building a future where every brilliant mind in this country, regardless of gender, has a chance to contribute fully. This is not a fairness issue; it's an economic imperative. Let's close the gap and unleash the full promise of America. Thank you.

[19:54] Corey Clark: (cross-examination) Um, I don't disagree with almost anything you said... but almost all of your arguments were for including women in science. They were not for gender equity; they were about making sure that when women are talented, that they're able to participate fully and contribute. Uh, is there any reason to believe that we need to establish equal representation across all disciplines, or is it really just about, you know, when women want to join in?

Pamela McCaulay: Well, first I want a clarification. You said my points were about including women, not about gender equity. Will you tell me how you—

Corey Clark: They weren't about statistical parity. Do you believe it should be, in all fields, it should be 50/50 men—

Pamela McCaulay: Do I believe it should be statistical parity? I believe that what we're doing is we are leaving talent on the field. So if you've got talent that you can access and you're not—

Christina Hoff Sommers: Would you agree that we're leaving a lot of young men behind as well?

Pamela McCaulay: I would agree that we're leaving some young men behind. However, the young men don't face the same barriers as the women do.

Christina Hoff Sommers: But you said our colleges are now 59% female.

Pamela McCaulay: I wasn't talking—that's not the case in STEM. 59% is... 59% of women are graduating from college, I believe that's a statistic I referenced, but we're talking STEM here... You heard the statistics on computer science, you heard the statistics on engineering, the statistics in math and physics are similar. So we cannot say that we have achieved parity whatsoever.

Corey Clark: The issue is, are you asserting that parity is the thing that drives innovation, or is it simply enough to open the doors to women, let them participate, and their percentage—15, 20, 25, 30, 35%—these are all valuable contributions. We don't need perfect 50/50 representation.

Pamela McCaulay: No, because I think my comments were very clear. Uh, it is clear that there are barriers that persist that prevent women from entering STEM and also from succeeding... so am I saying that... it's not enough for us to say that you can come and get a STEM degree when we're not making efforts to create an environment that will allow them to flourish and succeed.

[22:45] Corey Clark: (opening statement) I think everybody on this stage agrees that the inclusion of women in STEM has contributed to scientific and ethical progress... Everyone agrees that women deserve equal opportunities, and everyone agrees that women who are interested in STEM should be encouraged and supported... The debate is not about inclusion and encouragement of women. It is about closing the gap. It is about pursuing equal outcomes in STEM.

This goal, the pursuit of equity, is based on the false assumption that current sex differences result from oppression and other barriers against women. Instead, these sex differences are the outcome of a free society where men and women pursue their strengths and interests. Pursuit of equity undermines this freedom and requires intolerable top-down social engineering that pushes both men and women further away from their goals.

One of the most robust and broadly true findings in psychology is that girls and women are relatively more interested in people, and boys and men are relatively more interested in things. And so women tend to be attracted to organic fields of study such as social sciences, humanities, biology, and medicine. And men are relatively attracted to inorganic fields of study such as engineering and the physical sciences. When educational and career opportunities opened to women decades ago, they made rapid progress and have surpassed men in the disciplines that interested them... They have not reached parity with men in physics and engineering not because sex barriers were held up in only these disciplines... but because women on average have less interest in these disciplines. This is not a deficiency of women, and it is not a deficiency of society that needs to be corrected.

Sex differences in STEM emerge not from the oppression of women, but from their liberation. The gender equality paradox shows that psychological sex differences, including educational and occupational sex disparities in STEM, are larger, not smaller, in countries with higher sex equality and rights and freedoms... How then do we achieve equity in STEM? This requires top-down social engineering that is a mix of soft coercion against women and illegal sex discrimination against men...

Perhaps the most referenced paper for claiming that it is women who suffer sex-based discrimination in STEM is one by Moss-Racusin and colleagues from 2012... But a much more recent study by Honeycutt and colleagues with a sample size 10 times larger found precisely the opposite. And in fact, the female applicant was favored across all domains... Hiring biases in tenure-track STEM favor women. These same reverse discrimination patterns are observed in real-world outcomes. When men and women apply for tenure-track jobs in STEM, women are at least as or more likely to get hired than men, even when the men had stronger applications...

Why this moral regress? Because this is what it takes to force equity. Not many women apply for these jobs, so to achieve equal representation of women, we have to discriminate against men. And so we do... Why should young men today suffer discrimination because young men in 1970 received certain advantages? This response—writing past wrongs by committing more wrongs—plagues a new generation with old problems... In a just society where men and women are free... we will not have perfect parity in STEM. This is not a tragedy in need of correction. It is instead the true benefit of diversity.

[30:41] Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: (cross-examination) Thank you for those remarks. Um, I have just a couple of questions. Um, uh, the first is, are you suggesting that girls are inherently less interested in STEM?

Corey Clark: They are, yes. Not all STEM. They're less interested in, um, the inorganic fields, like particular branches of engineering and physical sciences.

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: So you've referred to those as, uh, masculine interests or male interests, and I just want to know what you're basing that assumption on.

Corey Clark: The National... I wouldn't trust an advocacy organization to study this.

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: It's an NSF-sponsored program, and the data and the reports are NSF-sponsored... we have found that most girls up until the age of around 12... have equal interest in, uh, things that you've now referred to as masculine subjects... and that it isn't until the social constructs of middle school and then high school that they begin to be dissuaded from these.

Corey Clark: Well, there might be studies showing that is not true, but there are a lot of studies showing that that is true... David... Lubinski... he studies mathematically precocious youth, starting with 12-year-olds, but tracking their, um, progress over time. And this is including girls and women that are extremely mathematically talented, but they still have, relative to men, they have more, uh, interests aligned with female interests.

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: The fact that you call those masculine, that is a societal expectation...

Corey Clark: No, what you did is what the problem is... societal expectations and what we believe are male fields... those are things that discourage young girls.

Christina Hoff Sommers: But almost every field in academia was once a male field, and women defied... men dominated in every academic field until the 1970s or 80s... and there were many areas where women just went in and redefined...

[33:44] Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: (opening statement) Um, so I'd like you for a moment, um, to imagine a world where our greatest challenges—climate change, pandemics, global food insecurity—all of these problems are only being tackled by half of the available talent. That's what happens when women are excluded from science, technology, engineering, and math... To tackle the world's pressing challenges, we need her voice. We need her creativity and her leadership in STEM.

My first point is about economic empowerment and financial independence. STEM careers offer some of the highest paying, fastest-growing jobs in the world. The median wage for STEM jobs is more than double that of non-STEM roles... On average, STEM professionals earn about twice what the average job or wage earner in the United States earns. So that's about $90,000 to about $45,000 for non-STEM occupations.

The next point I want to make is the idea that a seat at the table leads to professional growth and systemic change... Income is not everything. Representation matters. When women are included in STEM, especially in leadership roles, the benefits go far beyond the individual. Having a seat at the table means influencing the decisions. This means influencing how clinical trials are done, how clinical trials are designed, who to include in those clinical trials, what technologies get funded, what problems get solved.

And finally, I want to talk about inspiring the next generation... Girls need role models in STEM to envision their future. Exposure to female mentors doubles the likelihood of girls pursuing STEM careers... Let's not call these masculine or feminine interests. Let's call them interests in science. But if you don't see it, it is harder to be it... A recent Microsoft study found that girls with access to female STEM mentors were more than twice as likely to pursue a career in STEM themselves.

In conclusion... this is not just a matter of statistics. This is a matter of justice. Girls grow up being told they can be anything, and yet too many doors in STEM are still locked or, worse, pretend to be open while biased systems decide otherwise. Closing the gender gap in STEM is not a favor to women, and it does not disadvantage men. It's a responsibility to fairness, to equity, and to the future.

[42:34] Christina Hoff Sommers: (cross-examination) What is the evidence that girls are being held back in STEM?

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: I mentioned that... the National Girls Collaborative Project, but also the National Science Foundation publishes a report every year... that shows that girls are actively being discouraged.

Christina Hoff Sommers: Who discourages them?

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: Their teachers, their peers—most definitely their peers... their parents, uh, societal constructs that say that these are masculine interests and not feminine interests.

Christina Hoff Sommers: Yet 60% of the biology majors are female and, uh, 56% of chemistry majors are female. Why weren't they discouraged? What happened there?

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: So I think it is correct that in biology and the life sciences, there's probably equal gender parity... but that is not true in math, it's not true in engineering, computer science... The question is, why are teachers and parents and peers saying, "Don't do physics, but do biology?"

Christina Hoff Sommers: Or become a doctor, but don't become a physicist.

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: We are comfortable encouraging women to become doctors and caretakers, societally speaking... those are can be women and feminine fields. So chemistry and biology, those are very much the forerunners to that of a career in medicine. Unlike engineering...

Christina Hoff Sommers: And do you think that, like today, 80% of the majors in psychology are female? Do you think men are getting messages that they shouldn't go into that field?

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: That's not what the debate's about... what we're talking about is engineering, computer science, mathematics. There is without question... barriers and systemic issues in place that discourage from the time they're girls into the time they're in college and even into the workforce.

[45:45] Christina Hoff Sommers: (opening statement) Well, good evening... I oppose the resolution that we must close the gender gap in STEM because I find it outdated, unjust, and counterproductive. It's 2025, not 1970. Look around. The educational landscape has changed. Women have not merely closed gaps in key areas of STEM; they're doing better than men... They have all but overtaken the social sciences. Women... in 1970, it was about 6% of women were medical students. Today, it's 55%. Veterinary schools, once overwhelmingly male, are now more than 80% women.

Now, men do outnumber women in computer science and engineering... but these are outliers. The broader trends show women dominating higher education, now earning a majority of associate, bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees. Today, we are doing a far better job motivating, engaging, and preparing young women for college and the modern workplace. Today, increasingly, young men are the second sex in education... I urge you to visit the website of the American Institute for Boys and Men at the Brookings Institution. Just look at the latest data on male deficits in literacy, school engagement, college attendance, degree attainment, workplace participation. These gaps, which threaten to become a chasm, these are tragedies for young men and portend social and economic chaos for our society.

But the gender equity movement deploys an unusual logic. Gaps favoring men, those are evidence of invidious discrimination... Gaps favoring women, no matter how large... those go unmentioned, unaddressed.

I just don't see evidence [women are suffering from discrimination]... If it's true that, um, bias and stereotypes, lack of role models, these are primary barriers to women's achievement today, why didn't they stop women from advancing in biology, veterinary medicine, psychology, and all the other fields once dominated by men?

One of the best explanations that I've heard for, uh, why there are more men in engineering and computer science... has nothing to do with bias or discrimination... researchers looked at 1,500 college-bound seniors... they found that students with strong math and verbal skills, male or female, they were less likely to be in a STEM field than a field that drew on their communication capacities. But here's what's relevant... Young men were twice as likely as young women to be mathematically strong and verbally weak. Seventy percent more young women than the young men excelled in both areas... It could be that women are less numerous in science and tech not because of bias and oppression, but because more fields compete for their interests. The career pursuits of high-math-ability males may be attributable to their narrower options.

We should try to make all fields open and welcoming... but right now, it's boys and young men who need the most help. So I suggest that we amend the motion... Instead of striving to close the gender gap in STEM, let's try to assure equal opportunity for all. Thank you.

[54:46] Pamela McCaulay: (cross-examination) Uh, thank you for your remarks. Um, can you, uh, explain to me why you think it's acceptable that fields critical to future innovation, like AI, uh, data science, biotech, remain predominantly male-dominated?

Christina Hoff Sommers: I would be concerned if there were no women in these fields, but there are brilliant women who are in engineering and, uh, who are working in AI. It's not that women aren't there. What you're demanding is 50/50. I want the best people there. And I think that... all the evidence suggests that we are missing out on vast numbers of young men who aren't even competing because they're not even getting into college. So... let's do it for both girls and boys.

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: But you're assuming that a truly merit-based system, our meritocracy, is actually equal... and that women are facing documented systemic barriers in STEM, which they are, um, such as bias in hiring...

Christina Hoff Sommers: Yes, except bias favors women in hiring. Yes. I mean, if I could share my reference...

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: We can have dueling studies, but ours are more rigorous.

Christina Hoff Sommers: But, okay, go... The numbers don't support your position, ladies. It's not there.

[56:58] Rebuttals

Pamela McCaulay (Affirmative): We know that STEM jobs are projected to grow 10.4% between 2023 and 2033, almost three times faster than non-STEM jobs. So if we're talking about closing the gender gap in STEM, we're not talking about charity, folks. We're talking about strategy. We're talking about survival... If we close the STEM gender gap, we can add $299 billion to our economy in just 10 years... Our competitors around the world are investing in all of their people. And meanwhile, we're leaving brilliance untapped, innovation unrealized, and prosperity unclaimed.

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield (Affirmative): First, it empowers women financially... Second, it creates leadership and change. Women with a seat at the table have greater, uh, influence... Third, it inspires future generations. When girls see women in STEM, they believe it's possible... This does not exclude men; it simply invites women to the table.

Christina Hoff Sommers (Negative): They are demanding... statistical parity between men and women in STEM, which is a quota. It's based on the assumption that, um, that the absolute equality between women and men in all fields is a reasonable goal. But what if men and women on average don't share identical interests and aspirations? ...We have spent the last quarter of a century... an unbelievable amount of activism around closing the gaps, uh, where girls were lagging behind. They've caught up... now it's time to do something for the boys, and I just hear no support for that... Anyone who takes a serious look at what is happening in education has to be concerned about young men... It's not a gender war. It's not a zero-sum game... So I suggest once again that we could amend the motion... instead of striving to close the gender gap in STEM, let's try to assure equal opportunity for men and women.

Corey Clark (Negative): I have not heard one argument yet for closing the gender gap, uh, for parity or equal representation. I've heard arguments for inclusion, which we support... The issue is this obsession with parity and equity and equal representation, which might not occur naturally. And given that the differences we observe in STEM are perfectly aligned with differences in explicitly stated preferences by men and women... and that these differences get larger when... women are more free, the differences get larger. All of this suggests this is women exerting their will, and they're doing great, and they're killing it. And I think things are pretty good for women.

[1:06:32] Audience Q&A

Linda Rivia: Well, thank you very much to our speakers... So we have time for Q&A... I would like to throw it open to the audience right away.

[1:07:16] Audience Member: Hi, this was excellent... So I want to ask the negative side question— uh, to start with just a simple question. Is—would you agree with... the affirmative side that there are, in fact, uh, sex differences in inclinations, preferences, not necessarily skills, but interests? Uh, is that something you'd agree with, or... do you think that any differences that do exist, for instance, are purely a result, say, of, uh, social influences?

Linda Rivia: I think you're asking the affirmative side.

Audience Member: Sorry, yes.

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: Um, so... I do, I'm a biochemist by training, so I do believe that there's biochemical differences and there are gender differences in inclination... but I think collectively, at a certain point in time, girls are actively discouraged from pursuing interests in math and science. And it is that piece that really bothers me. Because even if there are small differences in their inclination... whether you want to build Legos to build a hospital or build Legos to build a rocket ship, you still want to build Legos. You still want to be an engineer. And so when you actively discourage that, then you may lose some of those talented people.

[1:12:55] Audience Member: I am a professional woman in science. I founded a company, was CEO, I am on the boards of five companies. I am routinely the only woman in the room... at the higher levels, do you have a question? Tremendous barriers... Why is it that the barriers are still there in the upper levels in business?

Corey Clark: Um, I think probably most of this is not due to barriers... Part of it is what Christina mentioned... the higher standard deviation among men. And so if you look in the top 0.01% on almost anything, there are 10 times more men than there are women there. Also, there are massive differences in how many hours men and women want to work... men are greatly overrepresented among people who want to work 60, 70, 80 hours a week. And so when you're talking about people who work 80 hours a week and who have a 170 IQ, like, not many women are going to fit that profile. They don't want to. They don't want to spend their whole entire life in their office.

Pamela McCaulay: Women entrepreneurs get funded at a tenth the rate that men entrepreneurs do by venture capitalists. It is—there are still systemic barriers here.

[1:16:04] Audience Member: I was surprised to hear from neither side discussion of parenting... Could it be the case that there aren't top-down barriers... but women are choosing it out of free choice... acknowledging that STEM jobs are so demanding that they would withdraw to have more of a parenting focus?

Christina Hoff Sommers: One from each team... I've seen a lot of data, but most recently from the Pew Research Institute looking at preferences... about 20% of women who are high-octane careerists... 20% who would prefer to stay home and not work at all, and then 60% are... adaptives... Men and women have different preferences about how they arrange their lives. And I would like to be a society that respected people's choices... It's not just a given that this is a bad thing that women have these preferences.

Pamela McCaulay: I'm glad you mentioned the parenting... you're young, I got my first engineering degree before you were born. Okay? And so women were working 40, 50, 60 hours a week easily then. Work-life balance did not exist. And so I don't think that is necessarily today... I am truly very pleased as a dean to have a work-life balance approach to my college so that my male and female faculty can all, uh, leave to pick their kid up from school because I still know they're going to do a great job.

[1:19:56] Audience Member: Question for the affirmative team. Uh, you portray a picture of rapidly growing demand for talent and need to add lots of more people. Yet you seem to have very little, um, confidence in the ability of grasping, aggressive, competitive, selfish businesses to go wherever they need to go to get that talent. Could you comment on your apparent lack of, uh, confidence in private sector competition and initiative?

Pamela McCaulay: Well... we did note that private sector can be aggressive at going to get talent, and that in many cases that means attracting international talent... That said, the private sector can't do it alone. There are too many systemic barriers in place... So I'm not minimizing the private sector's ability to go out and get talent. The fact of the matter is that a lot of the talent that can be groomed and developed is not being developed... the private sector alone cannot do this. This needs to be a systemic effort.

[1:23:02] Audience Member: Hi, uh, have a question for the affirmative team... you've been talking about a lot of initiatives that you're trying to close the gender gap in college and grad school... how does that square with the kind of very limited number of spaces in colleges? As far as I know, MIT class size, for example, hasn't grown in ages.

Linda Rivia: The question is, how do you square "we want to increase the representation of women, we have nothing against men," but this is a zero-sum game?

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: Did you not hear the statistic that we're seeing a 10.4% increase in STEM jobs from 2023 to 2033? So there are more jobs than there are people, men or women, to take these jobs.

Audience Member: I'm not talking about the jobs, I'm talking about at the undergraduate level.

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: Right. So we're not arguing against meritocracy. We're saying that it isn't a meritocracy... that the systemic biases that exist are making it such that it's not an equal playing field. We are saying open up the field for everyone... This is not disadvantaging men. It's saying men have had a long time dominance from the 70s... and now to 2025. And what I'm saying is that we need to be sure that the field is open for all.

[1:25:30] Audience Member: Uh, thank you all for a very lively debate... something that comes to mind for me is the question... you talk about the need for mentorship and for examples for women, and I wonder what you think about... that pointing in the direction of gender segregation in education and even in the workplace? If the problem really is that women need to see other women... wouldn't that point in the direction of, uh, women teaching women in women's schools or women colleges?

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: That's an excellent question, and one that I grapple with often because Simmons University is a... small liberal arts college for women... and we talk about this all the time: are we training them in an artificial society...? But I think what's most important is that if you are mentoring young women... to develop their own voice... then they will be able to function at high levels in mixed environments... I don't think having them only be around women... creates a space for them where they are unable to navigate that mixed diverse community. I think, in fact, what it does is make them stronger individuals.

[1:28:53] Audience Member: So the question is going to be to the negative... Parents generally discourage both boys and girls from pursuing careers in prostitution, even when it's legal. Why should we accept that top-down social engineering of careers is necessarily negative, um, if we are in a time of mass social change... shouldn't we pursue social engineering to achieve the, uh, HR inputs required for solutions?

Corey Clark: The reason that it was bad in this case is because it's pushing women away from their talents and interests, and it's resulting in the discrimination against men. These are bad outcomes. There's no evidence that what we need, what makes disciplines and organizations work best, is having exactly 50/50 representation in everything... What are the benefits, what are the costs? And what we do know is happening is we're pushing women away from their interests and their talents, and we are discriminating against men.

[1:32:45] Audience Member: I have a question about systemic bias and social engineering, and it's an example that's been happening right here at MIT for 20 years, where they have successfully closed the gender gap in undergraduate representation... by having the acceptance rate for women be double the acceptance rate for male applicants... Is that social engineering, and is that systemic bias?

Christina Hoff Sommers: It could be that the females have... fewer applying but they have stronger records. We'd have to see their SATs.

Audience Member: Statistically... they never will release that data.

Corey Clark: It's statistically unlikely, yeah. Uh, so I would say that's very likely discrimination happening to get that pattern. Can't know for sure, but very likely.

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: Well, I'd go off script and say I would agree that that could be perceived as explicit bias... As the affirmative side, we're not saying those types of biased... acceptances are necessary. We're saying that at the time when young girls are developing their interest in STEM, that they are given the same opportunities as boys.

[1:35:15] Audience Member: Since it looks like I'm last, I'll be quick... is there any evidence or research looking at what percentage of women who attend single-sex elementary and secondary school education... go into the STEM fields as opposed to their percentage in... public mixed-sex schools?

Jennifer Rocklin Canfield: So at the undergraduate level, I don't have those studies in front of me, so I apologize. But there are a number of studies that show that particularly for STEM majors coming out of women's colleges, they do, uh, tend to go on to whatever the next career step is... So those are the numbers that I have. I don't have them here, so I apologize, but there are... quite a few studies that show single-sex institution for women who study STEM, they do better and their outcomes are better.

[1:37:33] Linda Rivia: All right, I think... with that, uh, I want to thank very much for our guests for, uh, an enlightening, lively, vigorous... it lived up to our, uh, to our requirements, debate. So please join me in thanking everybody. And also, if you wouldn't mind, um, please, uh, use that, uh, scan the QR code and fill out a survey. And with that, I bring this debate to a close. Thank you all for coming. (Applause)